Monday Masterclass: secondary worlds

Definition

On the face of it, a secondary world is easy enough to define: a made-up world that is completely different from our own world, created by an author as the setting of a story. Terms such as ‘constructed world’, ‘fantasy world’ and ‘fictional world’ are partly synonymous with ‘secondary world’.

The expression was first used by Tolkien in his essay, ‘On Fairy-Stories’, an attempt to define and defend the fantasy genre. A fairy-story, according to Tolkien, is not merely one that contains fairies, elves or similar tropes, but one that concerns the Perlious Realm, fairy-land. A fairy-story is not a traveller’s tale, such as Gulliver’s Travels, nor is it a ‘beast fable’, a story with talking animals, like ‘The Three Little Pigs’, even though such tales contain definite fantasy or fairy-like elements.

The key thing is that the existence of Lilliputians or Brer Rabbit within a world that is supposedly our own (primary) world, requires a suspension of disbelief. In contrast, the skilled author of a secondary world (the ‘sub-creator’ of a ‘sub-creation’) is able to construct a logically consistent realm

which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside. If you are obliged, by kindliness or circumstance, to stay, then disbelief must be suspended (or stifled), otherwise listening and looking would become intolerable. But this suspension of disbelief is a substitute for the genuine thing, a subterfuge we use when condescending to games or make-believe, or when trying (more or less willingly) to find what virtue we can in the work of an art that has for us failed.

So far, so good. But the picture, I think, isn’t nearly so simple. There is a sense in which all fiction takes place a secondary world. The world of the Harry Potter books clearly shares much with our own world – but it is equally clearly not our own world. The London of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories is even closer to what we would understand as our own reality – except that there were no Holmes, Watson, Lestrade or Moriarty in Victorian England.

One could argue still further that even the truest history is only a version, an interpretation of what happened in reality, that the historian’s research and understanding mediated through his writing, mediated still further through the reader’s comprehension, results in enough difference from fact – or at least ambiguity – to constitute a secondary world.

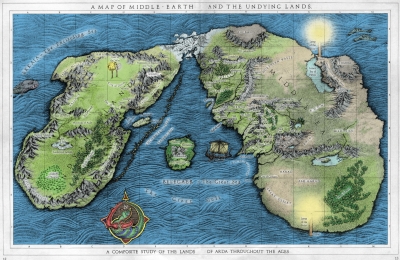

The concept of a secondary world is nuanced still further by the fact that no author operates within a conceptual vacuum: no secondary world can hope to be truly original and therefore independent of the real world because everything a writer creates must be based on something, whether it’s history or other fiction. The legendarium of Arda, the world of Middle Earth, is based on northern European mythology; if it truly were a secondary world, such links would be impossible. Like the biblical Eve being formed from Adam’s rib, Arda is made from the flesh our own world.

In addition, Tolkien and other writers have posited or hinted that their secondary worlds are versions of our own world, either as alternate histories, the distant past or the far future. Other writers have used framing devices that imply that our own primary world and their secondary world exist side by side, in parallel dimensions that can be reached through magic, dream or a mysterious portal.

A secondary world does not have to be a fantasy world – that is, one that contains magic. Science fiction abounds with fictional realms as much as fantasy.

I wonder whether it may be worth refining the term ‘secondary world’ with a few qualifications to make its use more precise. For instance, we might call a fictional world that is completely removed from the real world a ‘pure’ secondary world. One that operates in another dimension that is somehow reachable from our own could be a ‘parallel’ secondary world. ‘Remote’ secondary worlds would be ones that take place in distant times or places (which we could further specify as ‘temporally remote’ or ‘spatially remote’).

An ‘adapted’ secondary world would be one that is spatially and temporally coterminous with our own, but in which important aspects have been changed – such as an alternate history or the presence of magic. A ‘modified’ secondary world would be similar to an adapted one, except that the degree of difference from the real world would be less drastic – for instance, the story could be set in a fictional town, but the history and laws of the world would be unchanged from what we know. Finally, where a fictional world is, to all intents and purposes, the same as the real world barring the events of the story, we might refer to it as a ‘close’ secondary world.

Some Secondary Worlds

Perhaps the earliest secondary worlds were the magical or divine realms of religion and tradition. The cosmologies of most religions have at least a few such parallel worlds – Christianity and other religions have Heaven and Hell (which latter might be further divided into Gehenna, Purgatory, the Limbo of the Fathers and the Limbo of the Infants); Buddhism has a similar hierarchy of realities including hell, the realm of hungry ghosts, the realm of animals, the realm of humans, the realm of low deities, to the realm of gods; Greek mythology contains such places as Olympus, the Garden of the Hesperides, Hyperborea, Nysa and the Elysian Fields; European mythology has such locales as the Norse Valhalla, the Irish Tir na nÓg and the Welsh Annwn.

The above probably don’t qualify as secondary worlds – at least in terms of being the deliberate creation of an author. However, Atlantis was likely invented by Plato (c 428-427 BCE – c 348-347 BCE) – possibly based on the destruction of cities by natural disasters – and used as the setting discussed in his dialogues Timaeus and Critias. The latter describes Atlantis in some detail as being the province of Poseidon, located in the Atlantic and being as large as Libya (ie, Africa) and Asia combined. Poseidon had a child with a mortal, and this child, Atlas, and his descendants ruled Atlantis until their divine blood was so weakened that they succumbed to mortal debasement and Zeus decided to punish them. The dialogue stops at this point, unfinished.

Medieval romance has a few secondary worlds. Arthurian legend as we know it, while based on folk tales and possibly historical figures, comes in large part from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s pseudohistorical History of the Kings of England, as well as from successive writers like Chrétien de Troyes and Thomas Malory. The presence of magical artefacts (the Grail and Excalibur), magical places (Avalon) and magical beings (Merlin and the Green Knight) make the world of Matter of Britain an adapted secondary world in my scheme.

The much less well known King Horn, a chivalric romance from the thirteenth century, is set in the fictional kingdom of Suddene and the characters travel by sea to the realm of Westernesse. Fantasy readers will, of course, recognise this as another name for Númenor; Tolkien took the name from King Horn.

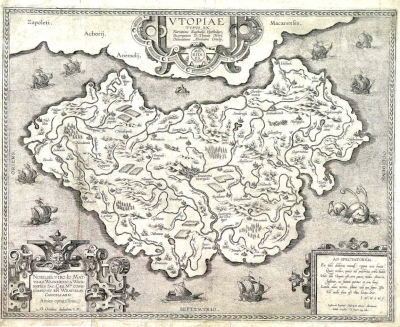

Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), is a detailed description of an idyllic communal, Humanist island society, possibly somewhere in the New World. The enlightened practises of the Utopians form a critique of European Church and society of the time (Martin Luther presented his 95 theses in 1517). The word ‘Utopia’ means ‘no-place’. Gulliver’s Travels (1726) is another satire set in remote lands; as is Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872; ‘Erewhon’ is an anagram of ‘nowhere’).

Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women is one of the earliest modern fantasies. In it, the main character, Anodos, finds out from a fairy hidden in a desk that he has fairy blood and is subsequently transported to Fairy Land, a land where fairies live in flowers and make them glow, and where the vengeful spirits of the Ash and Alder Trees are bent on killing Anodos.

William Morris, perhaps better known for his socialism and textile design, was also a key writer in the development of fantasy. Books such as The Wood Beyond the World and The Well at the World’s End are modelled on medieval romances in setting, story and language – which latter fact can make them a little hard to read. They differ from much proto-fantasy by being set in pure secondary worlds rather than related to our own by some means.

In E R Eddison’s The Worm Ourboros (1922), the story revolves around a war between the Demons of Demonland and the Witches of Witchland – all of whom are human: the names are just names. The story is framed at the beginning with the story of a man here on Earth who is granted a vision of the events unfolding on Mercury – a science fictional device which is completely pointless and isn’t even returned to at the end of the novel.

In The King of Elfland’s Daughter (1924) by Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett (better known as Lord Dunsany), the hero, Alveric, travels to Elfland to woo the elf princess Lirazel; in Elfland, however, times moves much more slowly – and this leads to heartbreak when the couple return.

From here on we tread on more familiar territory. The Hyborean Age of Robert E Howard’s Conan stories is an alternate past of our own world, as is Middle Earth, as I mentioned above. Other, more recent fantasies that are set in a secondary world of the remote past are Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time series (which, because time is a wheel, and continually repeats itself, is also set in the distant future), and Charles R Saunders’ Imaro series – works by a black author set in a fictional ancient Africa.

Twentieth century fantasists have often followed in the vein of C S Lewis’s Narnia stories by having heroes transplanted from the real world into a fantasy world – examples include The Fionavar Tapestry by Guy Gavriel Kay, one of the best post-Tolkien fantasies, and The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant by Stephen R Donaldson.

Latterly, it has become more common for writers to eschew any connection at all with the primary world, so Steven Erikson’s The Malazan Book of the Fallen, George R R Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire and R Scott Bakker’s Second Apocalypse (to name three of my favourites) all takes place in what I’ve called pure secondary worlds. On the other hand, even more latterly, with the rise of urban fantasy, that connection with our own reality has been established even more firmly.

The idea of the secondary world goes hand in hand with fantasy more than any other genre of fiction – largely thanks to Tolkien coining the phrase. It is even somewhat difficult to conceive of fantasy as taking place in anything other than a world with a different history, geography, society from our own, even different sentient races and different laws of nature (ie, magic).

I wish I had time and space to describe more such fictional realms, and in greater detail. Maybe that will be the topic of future Masterclasses.

What are your favourite secondary worlds?